Autonomic surveillance: what can polyvagal theory teach us?

HOW IS THE human condition under the pandemic corona times we are all facing, different from the usual predicament of humanity, which requires our going about our lives, while knowing, somewhere in the depths of our subconscious, that death may be just around the corner?

Surely, the thought that all it takes is a fatal road accident or a sudden, life-threatening medical event, sometimes comes to mind, whether as we witness such occurrences or undergo them ourselves. And yet, in normal times, most of us succeed in going about our lives as if we had all the time in the world. We may create various contingency plans, take out medical insurance, consult an estate-planning lawyer, revise our wills or even formulate a living will, appoint a trustee for our children, periodically strive to adopt healthier lifestyle solutions. But in so doing, for the most part, we do not succumb to catastrophic thinking, but rather, take things in stride and keep moving along the trajectories of the goals and ambitions we have mapped out for ourselves. To do so, requires defense mechanisms in working order, a healthy dose of denial or disavowal.

This may be a good place to discuss what constitutes unhealthy denial.

Let us take the case of someone whose physical symptoms require testing, perhaps to rule out some form of cancer. Unhealthy denial means burying one’s head in the sand, and not pursuing the proposed tests that are necessary for an early diagnosis and timely treatment. This form of denial clearly puts the person at risk. A healthy dose of denial means undergoing the proposed tests and yet somehow allowing oneself to take things in stride, without losing a sense of proportion and succumbing to an all-enveloping feeling it is necessarily the end of the world. This requires us to have access to our inner resources of hope and to the extent possible, belief in a higher power (nature, religion, other).

During the pandemic that is transforming the world as we know it, we resort to the same protective measures to minimize, deny or disavow the danger at our very door, not knowing if the virus is already within our home or person. And yet, the epic proportions of life and death in the shadow of the corona virus, the staggering and exponential amounts of infections and deaths in countries such as Italy and China as well in our own domicile, the continuous bombardment by the media with dire predictions and vivid images, whether on TV or other screens, hard as they are to fully grasp, are of such intensity and strength that they challenge and and at times threaten to overturn any defensive measures we may normally employ to keep our fears at bay.

Neuroception is a term coined by Stephan Porges, the scientist behind polyvagal theory [1] , a theory of how our autonomic nervous system works. During the past few years, polyvagal theory has been further elaborated and applied to treatment (e.g., Dana, 2018).

This term comprises two concepts—neuro and perception. Since neuroception refers to an innate process that occurs automatically, it does not involve perception, which would require consciousness. We have an autonomic, built-in surveillance system—neuroception is reflexive and automatic, without the need for an awareness of cues. Before our brain has had time to take stock of what is happening, the autonomic nervous system has already assessed the situation and initiated a response. The autonomic nervous system, in close two-way communication with the central nervous system and the rest of the body (e.g., HPA axis), assesses risk and takes action accordingly. This process takes into account information from the outside world as well as that from the inside—our bodies (e.g., heart, lungs, intestines).

There are three neurally-based states underlying how we react.

Each one is mediated by a different branch of the autonomic nervous system: the ventral vagal branch, which is associated with social engagement and connection; the sympathetic banch, associated with mobilization and action patterns of fight or flight; the dorsal vagal branch, associated with freeze, dissociation, immobilization, collapse, shutdown.

Neuroception results in gut feelings that indicate where we are on the continuum between safety and needing to respond to threat for our survival. It shifts our overall state, colors our experience—even when we are not aware of the stimulus evoking our somatosensory response. When we register cues of safety, we relax; when we receive cues of danger, we react accordingly.

We communicate primary emotions through facial expressions—our face is like a switchboard [2]. Our eyes search for and send signs of friendship, safety or conversely, danger, as do our ears, which are attuned to the cadence or music of speech, its underlying patterns and rhythms, its pitch and modulations, all of which reflect the underlying tone, streaming beneath and between our words. When the neuroception is one of safety, both sympathetic and dorsal vagal systems are inhibited, and the ventral vagal system takes dominance, the social engagement system associated with a ventral vagal state taking front stage. In contrast, when the neuroception is of a lack of safety and of imminent danger, we will see sympathetic mobilization e.g., Fight of Flight action patterns, or dorsal vagal Freeze or Collapse.

Neuroception > state > response

Safety (ventral vagal dominance) & social connection and engagement

Danger (sympathetic or dorsal vagal dominance) & Fight, Flight, Freeze

Under certain conditions, our neuroception is out of sync with the situation at hand, a problematic state of affairs. Some people cannot feel safe because their defense systems continue working, are not inhibited when they probably could. For example, a person who was molested or raped may not feel safe with their chosen partner, despite trusting him or her. In contrast, others do not experience danger when it would be appropriate to do so. Their defense systems are not activated in risky environments. Perhaps this accounts for why so many young people on spring break in Florida recently refused to heed the dire warning signs of the Coronavirus, willfully and flagantly ignored the authorities’ request for social distancing, and insisted on continued partying. Similar responses were evident in the United Kingdom, especially among staunch pub goers who could not imagine foregoing this habit.

When our neural expectations are disrupted, we experience an autonomic reaction, whether a positive experience or a negative one. Porges refers to this as “biological rudeness.” Neuroception can switch from safety to danger (or vice versa) in the blink of an eyelid.

The current pandemic has disrupted our neural expectations, and our familiar world has become topsy turvy.

People who were hitherto safe may no longer be so, as the invisible enemy may stealthily and insidiously invade our home and our body, without our knowing it. People may unwittingly be carriers despite feeling fine. Despite our efforts to keep the virus at bay by observing the new imperatives of these corona times, adjusting to new hygienic practices and observing social distance to the best of our ability, like an uninvited wedding guest, the coronavirus makes itself at home, only to attack without warning. Our daily routines at work, at home, with friends—all these have been derailed; our financial security, scant as it may have been, is now in question for millons of people who suddenly find themselves without work and are at their wit’s end as to how to pay their bills, their mortgage, their taxes, and how to continue to care for those who depend on them for sustenance.

We are at war with an invisible enemy, and there is no insurance policy that we will, in fact, survive, that we will not face death even sooner than we had reckoned, either our own, or that of someone we love fiercely. We do not know how long this uncertain corona time will last, what additional measures will be taken by the state to combat this plague, how this will affect us. This uncertainty is hard to tolerate, and we deal with in in various ways, both protective and defensive, both adaptively and less so.

We can only catch glimpses of what we fear, because, as the poet said, we cannot tolerate more than that. Consider Haim Nachman’s Bialik’s essay, Giluy Vekissuy Balashon (which to the best of my knowledge, has not been translated into English, but is well worth making the effort to read). Annihilation anxiety refers to an intense emotional experience of danger to one’s very existence.

Can we maintain a sense of safety, of faith and optimism that we will, indeed, survive, as we face not only a lunatic whirlpool of instability that sweeps us into the trauma vortex, but also a very real and present danger, a concrete threat to our very existence, a time bomb ticking away?

If so, how—what will it take?

What resources do we need, as we begin to register internal signs of primal annihilation anxiety, much like those experienced by young babies who are wholly dependent on their caregivers for sustenance to survive? For surely, now, more than ever, each of us needs resources, by which I mean anything that will make us feel better, yet does not come with a price tag. Resources can be both internal and external, for example, a sense of humor, creativity, trust, hope; friends, family, sports, music, art etc. We need both kinds, and this is a good time to shore up on them, to refine or even learn new and creative ways of accessing our existing inner resources and using them to find or develop new ones.

Our resource bank can never be too full, and if we begin to actively look for even fleeting or minor moments that bring with them a smile to our lips, a deep diaphragmatic breath, a sense of calmness or safety, some small pleasure, we are on the right track. And despite the necessity to observe social distancing, it is important to maintain a sense of connectness with your loved ones, your friends and family, using whatever alternative means you can, for example video conferencing with Zoom or a phone call.

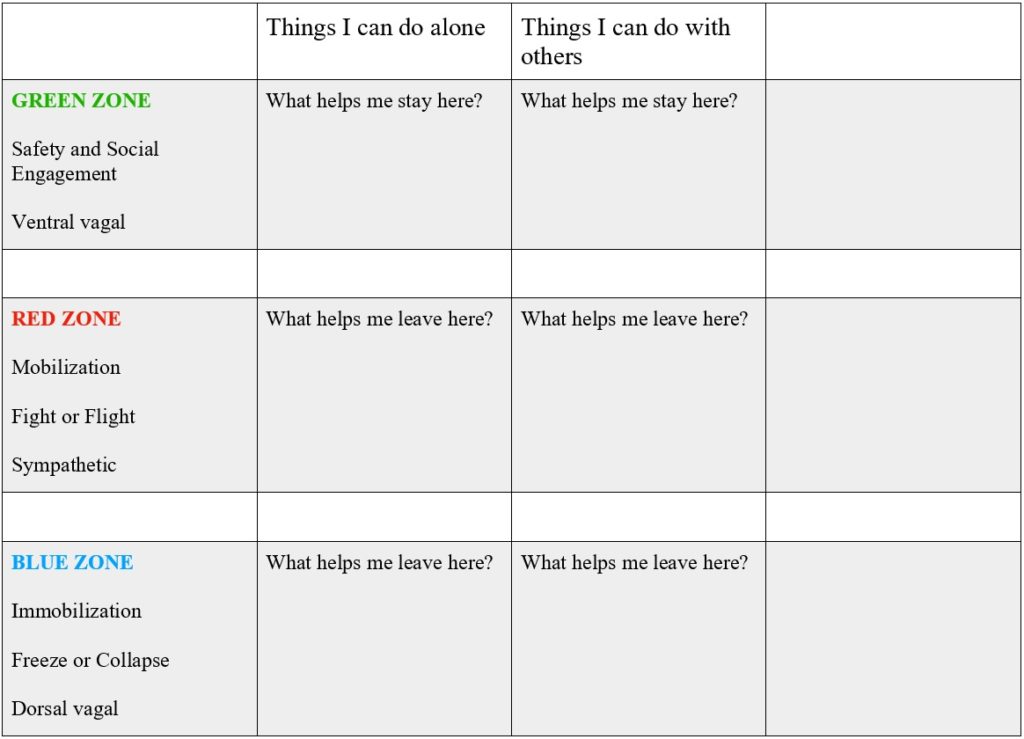

One thing well worth doing is learning how to track the state of your nervous system, and of that of those around you, such as your kids. I find it helpful to assign the colors green, red, and blue to how we experience our neural states, as discussed above. However, feel free to use whatever colors work for you or your kids. You may wish to utilize the following table to help you track the shifts in your daily neural states and to list what it is you need, to reach or remain in the green zone of safety and social engagement.

It is important to identify which neural state one is in, namely one of safety and social engagement, mobilization (associated with Fight or Flight), or immobilization (as evidenced by depression, tiredness, Freeze and/or Collapse).

Once you have a sense of where you stand on this ladder, you can either decide to prolong your stay there, if already within the green oasis of safety, or find ways of transitioning there, shifting from states of mobilization or immobilization.

Note that there are things you do on your own, or conversely, with others.

Each of us moves up and down this ladder numerous times per day. It is important to learn to identify how each neural state feels, and where you are, at a given moment, as well as what prompts you to switch from one to another, often in the blink of an eyelid.

This new skill is an important part of self-regulation (Dana, 2018).

The practice of somatic experiencing [3], a treatment method that, among other things, involves focusing [4] and a kind of somatic mindfulness, can be of great value in learning to more readily identify and change one’s neural state. It involves becoming increasingly aware of and attunded to your bodily sensations, both of constriction (e.g., tight, dense) and expansion (e.g., light, airy).

Other articles that may interest you:

1. Porges, S. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory. Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, Self-Regulation. New York: Norton

Dana, D. (2018). The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy. Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation. New York: Norton

2. Tomkins, S. S. (2008). Affect, Imagery, Consciousness. New York: Springer.

3. Levine, P. & Frederick, A. (1997) Waking the Tiger. Healing Trauma. Berkley, CA: North Atlantic Books & ERGOS Institute Press.

4. Gendlin, E.T. (1982). Focusing. New York: Bantam.